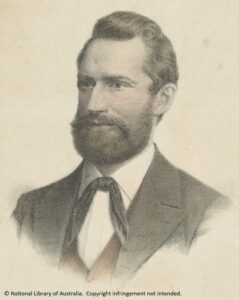

Dr Ludwig Leichhardt was the principal player in what must be one of the greatest scientific adventures in the history of European settlement of Australia. On 1st October 1844 he departed from Jimbour Station, the most western European station at that time in Queensland (Jimbour is just north of today’s township of Dalby on the Darling Downs in south east Queensland), to travel to Port Essington, approximately 300 km north east of Darwin. At that time, Pt. Essington was the only European settlement in northern Australia.

Dr Ludwig Leichhardt was the principal player in what must be one of the greatest scientific adventures in the history of European settlement of Australia. On 1st October 1844 he departed from Jimbour Station, the most western European station at that time in Queensland (Jimbour is just north of today’s township of Dalby on the Darling Downs in south east Queensland), to travel to Port Essington, approximately 300 km north east of Darwin. At that time, Pt. Essington was the only European settlement in northern Australia.

He arrived at Pt. Essington just prior to the wet season, on 17th December 1845, after traversing 4800 km. However, only seven men arrived at Pt. Essington – John Gilbert, an ornithologist and a protege of Gould, was speared and died at a camp near the Nassau River, not far from today’s Kowanyama on Cape York Peninsula.

He arrived at Pt. Essington just prior to the wet season, on 17th December 1845, after traversing 4800 km. However, only seven men arrived at Pt. Essington – John Gilbert, an ornithologist and a protege of Gould, was speared and died at a camp near the Nassau River, not far from today’s Kowanyama on Cape York Peninsula.

Leichhardt was a keen naturalist, and his diary is full of observations on plants, animals and geology. He was not a rich man, and had financed the expedition privately after government funding was withdrawn. On his return, he planned to sell many of his specimens to collectors in Europe in order to recoup some of his own expenditure on the journey.

However, on the 21st October 1845, just over one year since setting out from Jimbour Station and less than 2 months from their destination, disaster struck – three horses were drowned while crossing a creek beside the Roper River, near the modern township of Ngukurr, about 170 km east of Mataranka in the N.T.. Two days later, another horse drowned in a creek crossing.

The implication of these losses was enormous – Leichhardt was forced to abandon approximately 4000-5000 pressed specimens from the trip, as they did not have enough remaining animals to carry specimens and essential items like food and camping equipment.

Leichhardt wrote…

This disastrous event staggered me…The fruit of many a day’s work was consigned to the fire; and tears were in my eyes when I saw one of the most interesting results of my expedition vanish into smoke.

To William Philips, one of his companions, he estimated their monetary value to be £400-£500 (approx. $100, 000 in 2019).

The remainder of his specimens were consigned to a pack bullock. Two weeks later, they were approaching the south western tip of Arnhem Land, about 140 km north east of today’s township of Katherine. After travelling over rough sandstone country that tested their bullocks severely, the party entered a narrow gully with ‘some fine Nymphaea ponds and springs surrounded by ferns‘.

As Leichhardt related it…

Our bullocks had become so foot-sore, and were so oppressed by the excessive heat, that it was the greatest difficulty we could prevent them from rushing into the water with their loads.

One of them – that which carried the remainder of my botanical collection – watched his opportunity, and plunged into a deep pool, where he was quietly swimming about and enjoying himself, whilst I was almost crying with vexation at seeing all my plants thoroughly soaked.

So Leichhardt was reduced to tears twice in the space of a fortnight on account of his botanical collection! Indeed, Joseph Decaisne, who received some of these specimens at the Museum of Natural History in Paris, wrote that those he received were too badly damaged for exact study (Fensham et al., 2006), no doubt courtesy of the recalcitrant swimming bullock. Having spent countless hours myself collecting, pressing, labelling and recording plant specimens, I can still feel Leichhardt’s ‘vexation’ today!

Leichhardt’s legacy

Leichhardt’s expedition was one of the first to systematically sample such a large swathe of inland Australia, and the value of the samples he returned with, in addition to the detailed notes in his journal, were enormous.

Fensham et al. (2006) estimate the lost collection would have included well over 100 species new to science at that time, would have included a number of extensions to currently accepted ranges, and may have established as indigenous some flora species that are today thought to be exotic. They found…

Leichhardt may not have fulfilled his potential but commentators now regard Leichhardt as an extremely capable botanist who made a substantial and underrated contribution to the development of botanical knowledge in Australia…Leichhardt was a talented botanist and his significant contribution to Australian natural science should be recognised.

Glen McLaren retraced the Leichhardt journey in the early 1990s by horse, motorbike and eventually helicopter, and based a PhD on his findings. He summarised his findings on Leichhardt’s competency, both as a bushman and scientist, as follows (McLaren, My Greatest Regret, undated):

Firstly, armed with my navigational and cartographic findings I was able to state definitively that, given his paucity of equipment, Leichhardt’s mapping as well as latitudes and longitudes were most acceptable. He did not miss any major features.

Secondly, based on contemporary accounts, his journals and my field observations, Leichhardt’s bushmanship was unquestionably of the highest order, as he led the expedition the entire distance, selecting the route, finding water and securing campsites, often reconnoitering days in advance of the

main party and finding his way back through trackless forest at night.

And finally, time has shown that Leichhardt’s scientific field achievements were of the highest order. He was unquestionably the most broadly educated and complete field scientist in Australian exploration history. Indeed, he was a true polymath and heir to von Humboldt.

The above extract was taken from: http://leichhardt.qm.qld.gov.au/~/media/Microsites/Leichhardt/1001+words/mclaren-regret.pdf

Some Leichhardt facts

Some interesting facts about Leichhardt’s 1844-45 expedition include:

- To protect his specimens, he wrapped them with green hide, which when it dried shrunk and bound them tightly, acting to protect them from the damage they would otherwise have endured being tied to the back of a horse or bullock (a transportation technique that had already destroyed the ornithologist’s primary sampling tool, his best gun).

- Leichhardt commenced his epic journey with 17 horses and 18 pack bullocks – the latter carrying about 70 kg each. Loading these animals each morning took about 2 hours, and they often found (at least in the early days of the expedition) that the bullocks had strayed back to the campsite of the previous night, requiring someone (usually their native trackers, Charley and Brown) to retrace their steps and fetch them back (which then resulted in delays to departure of many hours).

- The party departed with 550 kg of flour, 90 kg of sugar, 35 kg of tea, 9 kg of gelatine and 12 kg of gunpowder. They lost a considerable amount of flour when they tried to cross a large patch of brigalow scrub within a week of departing – the many sharp sticks and shrubs ripped their bags to pieces, as they are still liable to do today!

- After this they always went around brigalow – however, Leichhardt encountered patches of brigalow and vine thicket that took days to skirt, indicative of the vast areas that once existed across central Queensland (in what is now called ‘the Brigalow Belt’).

- In addition to plant collecting, Leichhart had to determine the route to be taken through uncharted country (he generally scouted ahead, sometimes spending days away from the main party), drive, load and unload bullocks (sometimes several times a day), determine longitude and latitude (no GPS!), complete his log, account for and apportion dwindling provisions, take part in nightly watches (they were frequently the subject of attention from the indigenous peoples whose territories they were passing through), and provide leadership in relation to the various strains and tensions that inevitably develop in such a party on such a strenuous and lengthy expedition.

- Leichhardt had very little in the way of Flora’s to assist him in identifying plants (although even today, the only modern Flora to cover this area is the still incomplete Flora of Australia). His primary reference materials were Robert Brown’s Prodromus Florae Novae Hollandiae et Insulae Van-Diemen (1810) and Supplementum Primum Prodromi Florae Novae Hollandiae (1830), and de Candolle and de Candolle’s Prodromus systematis naturalis regni vegetablis.

- There are believed to be at least 2800 specimens collected by Leichhardt over his career in herbaria around the world, of which 78 have been designated as types. However, Fensham et al. (2006) located only 36 plant specimens from the 1844-45 expedition in Australian herbaria, and 16 from that expedition that may be held in Australian or European herbaria (although there may be more in the Paris Herbarium, to which he sent most of his specimens after the expedition).

- Leichhardt’s name has been honoured in at least 49 plant taxa, of which 21 are currently recognised names, including yellowjacket (Corymbia leichhardtii) – see below.

- Leichhardt’s route took him through or very near the site of a number of modern towns and landmarks, including Warra on the Warrego Highway (beside which he camped), Chinchilla, Barakula State Forest, Taroom, the Arcadia Valley, Rolleston, Comet, the Oaky Creek mine (just to the east of Tieri), the Saraji mine, Moranbah, the Goonyellah Riverside mine, through the gap in the Burton range where the current North Goonyella accomodation village is located (Ellensfield Rd), Glenden (he named the Suttor River), the Suttor mine, Belyando Crossing, Sellheim (just to the east of Charters Towers), Normanton, Boorrooloa, Roper Bar and the Cooinda Lodge at Yellowwater in Kakadu National Park. They crossed the current location of the Arnhem Highway about 20 km west of Jabiru.

- Even back then, wild buffalo were prevalent in the northern N.T. – Leichhardt noted numbers of buffalo as they neared Pt. Essington, and indeed their party managed to bring down a few (they were desperately short of food by then).

Leichhardt resources

For those interested in Leichhardt’s route, I recommend the Australian Dictionary of Biography website at http://adb.anu.edu.au/entity/8843.

This site has an interactive map of Leichhardt’s route in an embedded Google Earth display, with each campsite location and links to the diary entries of Leichhardt and a number of his companions for that day. You can follow his route exactly and read his observations and those of his companions as he traversed the country. In addition, the notes of Glen McLaren are available for each campsite.

I also recommend the following articles, on which I relied for some of the facts related in this blog:

Dowe, J.L., 2005, Ludwig Leichhardt’s Australian plant collections, 1842-1847. Austrobaileya 7(1): 151-163.

Dowe, J.L., 2005, Observations of Palms Made by the Botanist and Explorer Ludwig Leichhardt, During the Australian Overland Expedition of 1844-1845. Palms 49(4): 167-182.

Fensham, R.J., Bean, A.J., Dowe, J.L. and Dunlop, C.R., 2006, This disastrous event staggered me: Reconstructing the botany of Ludwig Leichhardt on the expedition from Moreton Bay to Port Essington, 1844-45. Cunninghamia 9(4): 451-506.

Glen McLaren also wrote a book on his findings in relation to Leichhardt:

McLaren, G., 1996, Beyond Leichhardt: Bushcraft and the Exploration of

Australia. Fremantle Arts Centre Press, South Fremantle.

Probably the definitive book on the disappearance of Leichhardt, and highly recommended, is that of Darrell Lewis:

Lewis, D., 2013, Where is Dr Leichhardt? The greatest mystery in Australian history. Monash University Publishing, Melbourne.

I don’t think the title of your article matches the content lol. Just kidding, mainly because I had some doubts after reading the article.

Your article helped me a lot, is there any more related content? Thanks!

Can you be more specific about the content of your article? After reading it, I still have some doubts. Hope you can help me.

You helped me a lot with this post. http://www.kayswell.com I love the subject and I hope you continue to write excellent articles like this.

코인선물거래소

EPL중계

EPL중계

https://shorturl.fm/CFLXD

https://shorturl.fm/C4FIA

https://shorturl.fm/1ev5A

https://shorturl.fm/h7ueB

Your article helped me a lot, is there any more related content? Thanks!

Your point of view caught my eye and was very interesting. Thanks. I have a question for you.

https://shorturl.fm/Y28P0

Can you be more specific about the content of your article? After reading it, I still have some doubts. Hope you can help me.

https://shorturl.fm/Q32IK

https://shorturl.fm/THSxk

https://shorturl.fm/9VjPN

https://shorturl.fm/MEDye

umsuka

Your point of view caught my eye and was very interesting. Thanks. I have a question for you.

Thanks for sharing. I read many of your blog posts, cool, your blog is very good.

https://shorturl.fm/pzWBK

https://shorturl.fm/LX8wY

Thanks for sharing. I read many of your blog posts, cool, your blog is very good.

Your point of view caught my eye and was very interesting. Thanks. I have a question for you. https://www.binance.info/pt-PT/register?ref=DB40ITMB

Your article helped me a lot, is there any more related content? Thanks!

https://shorturl.fm/6UCT5

https://shorturl.fm/VKshX

https://shorturl.fm/uJvlT

https://shorturl.fm/uRat6

https://shorturl.fm/BCNbo

https://shorturl.fm/QN98s

Thanks for sharing. I read many of your blog posts, cool, your blog is very good.

https://shorturl.fm/RNs7X

https://shorturl.fm/Happy

https://shorturl.fm/k0JWt

https://shorturl.fm/HJ3tc

https://shorturl.fm/z3Cgg

пленка защитная самоклеющаяся прозрачная пленка защитная самоклеющаяся прозрачная .

дизайнерская мебель для гостиной дизайнерская мебель для гостиной .

https://shorturl.fm/xKAcH

Thank you for your sharing. I am worried that I lack creative ideas. It is your article that makes me full of hope. Thank you. But, I have a question, can you help me?

https://shorturl.fm/wi6sb

https://shorturl.fm/B3os9

https://shorturl.fm/Xb93X

https://shorturl.fm/bHrT4

https://shorturl.fm/IsUCu

Your article helped me a lot, is there any more related content? Thanks!

https://shorturl.fm/vJ45p

https://shorturl.fm/A7Ot6

https://shorturl.fm/M0lUN

Thank you for your sharing. I am worried that I lack creative ideas. It is your article that makes me full of hope. Thank you. But, I have a question, can you help me?

https://shorturl.fm/gbPs0

https://shorturl.fm/USrhK

Your point of view caught my eye and was very interesting. Thanks. I have a question for you.

https://shorturl.fm/RvVBn

Your point of view caught my eye and was very interesting. Thanks. I have a question for you.

https://shorturl.fm/z1rEU

https://shorturl.fm/eM64w

Thanks for sharing. I read many of your blog posts, cool, your blog is very good.

https://shorturl.fm/mJEii

https://shorturl.fm/8Qc3b

https://shorturl.fm/4V1Ek

Can you be more specific about the content of your article? After reading it, I still have some doubts. Hope you can help me.

Your article helped me a lot, is there any more related content? Thanks!

https://shorturl.fm/6eCL3

Your article helped me a lot, is there any more related content? Thanks!

https://shorturl.fm/mqrkM

https://shorturl.fm/C1zio

https://shorturl.fm/rKm1f

https://shorturl.fm/hhnQc

https://shorturl.fm/gxXID

https://shorturl.fm/OXnZb

https://shorturl.fm/4zdQF

https://shorturl.fm/D8zJZ

Thank you, your article surprised me, there is such an excellent point of view. Thank you for sharing, I learned a lot.

https://shorturl.fm/J9mMI

Thank you for your sharing. I am worried that I lack creative ideas. It is your article that makes me full of hope. Thank you. But, I have a question, can you help me? https://www.binance.info/fr-AF/register-person?ref=JHQQKNKN

https://shorturl.fm/LbLIU

https://shorturl.fm/K51Ue

https://shorturl.fm/R8mk8

https://shorturl.fm/HmTRn

https://shorturl.fm/q1Vxs

https://shorturl.fm/rrd89

FB88UnitedStates, betting across the pond, eh? Wonder if they got the same footy odds…time to investigate! fb88unitedstates

Thanks for sharing. I read many of your blog posts, cool, your blog is very good.

https://shorturl.fm/GGY0C

https://shorturl.fm/l07FK

https://shorturl.fm/JRGci

Your article helped me a lot, is there any more related content? Thanks!

https://shorturl.fm/eyfdV

https://shorturl.fm/8LrjY

https://shorturl.fm/kl3gu

https://shorturl.fm/GLCtx

https://shorturl.fm/PzpZg

https://shorturl.fm/PdyBC

https://shorturl.fm/UioQH

https://shorturl.fm/fE6Rt

Your point of view caught my eye and was very interesting. Thanks. I have a question for you. https://www.binance.info/register?ref=IHJUI7TF

https://shorturl.fm/lK1TI

https://shorturl.fm/d0P0t

https://shorturl.fm/2QQQB